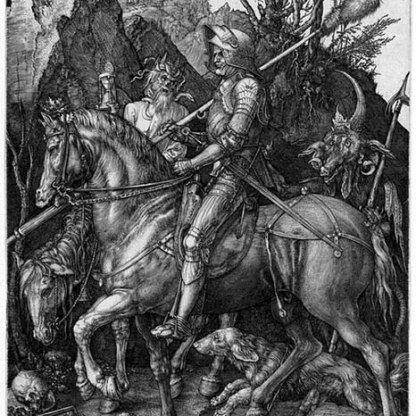

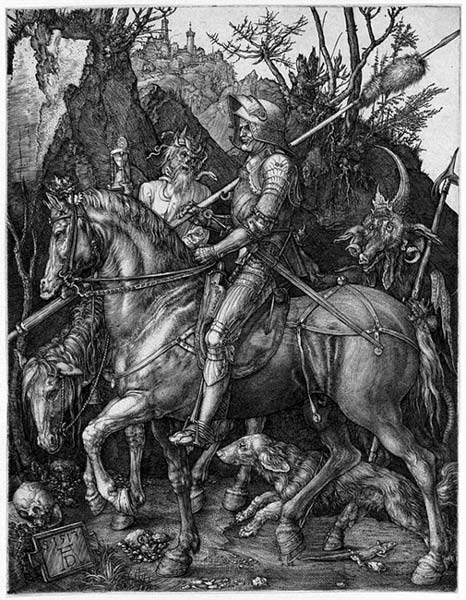

The Knight, Death and the Devil

In this brilliant depiction of calm, steely resistance to evil and mortality, the German artist Albrecht Dürer was probably influenced by the writings of his friend, the humanist philosopher Erasmus of Rotterdam who wrote in A Handbook for the Christian Soldier in 1504:

'Because you must fight three unfair enemies, the flesh, the devil and the world, this third rule shall be proposed to you: all those spooks and phantoms which come upon you as in the very gorges of Hades must be deemed for nought ...'

The comparison between the struggle of the Christian and that of the soldier goes back to St Paul's Letter to the Ephesians, 6, 11, where he calls upon the faithful to 'put on the whole armour of God, that ye may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil'. In this engraving, the idea receives its most brilliant visual expression.

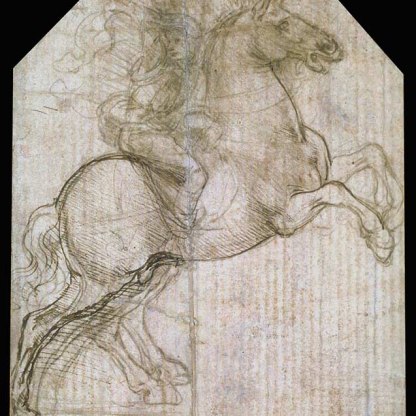

Dürer’s study of the horse alone is a remarkable work of anatomical observation. His appreciation of the proportions of the animal, of the way its body works in movement, is equal to that of his older Italian contemporary, Leonardo da Vinci. A horse and rider drawn by Leonardo in the Fitzwilliam can be seen right [PD.44-1999].

Dürer travelled extensively in Italy, and in Milan he would probably have had the opportunity to study Leonardo’s model for a great equestrian statue, planned as a memorial to Francesco Sforza. Like Leonardo, Dürer drew inspiration from the ancient bronze horses set up in the Piazza San Marco in Venice. There is a small sixteenth-century bronze copy of one of these in the Fitzwilliam, left [M.32-1997].

The details and the startling varieties of texture that Dürer suggests here show the great engraver at the height of his powers: the Knight’s panoply, which catches what little light there is in this sullen glade; the shaggy hound that runs alongside his master, as grittily determined as he, jumping to avoid the Devil’s cloven hoof.

The city in the background atop a steep, bare hill, might be a haven for the Knight. But the very landscape seems hostile to him, with its sharp rocks, its dark, exposed earth, its spiky, leafless trees and the lizard that darts beneath the horse’s hind legs.

Although these features distinguish the engraving as a masterpiece of naturalistic observation, it is arguably the fantastic elements that give the picture its power.

Death, to the Knight’s left, riding his own weary nag, holds up the traditional hourglass. But this is not the grinning skeleton that so often personifies man's mortality. This is something far more horrible – a rotting cadaver, more zombie than skeleton, whose worm-eaten flesh, skin and hair still cling to his bones. His lidless eyes stare vacantly at the Knight. His lipless mouth hangs insolently open.

In the handbook quoted above, Erasmus counsels his Christian soldier to take as a motto the biblical injunction 'look not behind thee'. Wise advice indeed to Dürer’s Knight, who is closely pursued by an almost comically grotesque Devil, a grim hybrid with a wolfish face, an alligator-like snout and teeth, ram’s horns, ass’s ears, and a huge single horn that recalls Dürer’s celebrated woodcut of a rhinoceros. In the murk at the very edge of the print we see the hint of a serpentine tail.

Two other engravings from the same period have been associated with this print to form a loosely connected triptych based around the idea of salvation. Both are, like The Knight, remarkable for their symbolic content and the technical virtuosity of their engraving. St Jerome in his Study and Melencolia I, left [P.3098-R], are generally thought to represent, respectively, the theological and the intellectual ways to salvation, while The Knight illustrates the moral path.

Like the Christian hero in Martin Schongauer’s late fifteenth-century print, The Temptation of St Anthony, left [1879.5.24.13], Dürer’s Knight is heroic in his indifference to the horrors that surround him.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Given

- Dates: 1862

Maker(s)

- Gamberucci, Cosimo Draughtsman

Note

Formerly attributed to Domenico Passignano

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…