Relics and Reliquaries

Where the bones of martyrs are buried, devils flee as from fire and unbearable torture.

St John Chrysostom

In the earliest written account of a Christian martyrdom, that of St Polycarp, a second-century bishop of Smyrna, we read that, after his execution and the cremation of his body, his followers gathered up his bones which were 'more precious... than the richest jewels and gold'. By the fourth century CE, the distribution and veneration of the earthly remains of martyrs was widespread. And from this time reliquaries of varying degrees of elaboration were made to contain them.

A relic might be part of a saint's body, or an object connected with him or her. Perhaps the most revered relic in the middle ages was the cross on which Christ had died. This had been miraculously discovered by St Helena, the mother of the first Christian emperor Constantine, around the year 326. By the middle ages pieces of 'The True Cross' were spread throughout Europe.

Theologians were keen to stress, however, that relics were not themselves objects of worship. They were rather, like icons, given reverence for what they represented. They were conduits of divine power rather than divine in themselves. As the great early Church Father St Jerome wrote in the fifth century:

We do not worship, we do not adore, for fear that we should bow down to the creature rather than the Creator, but we venerate the relics of the martyrs in order the better to adore Him whose martyrs they are.

The presence of relics in a church soon became obligatory. In the Book of Revelation, 6, 9, St John records that he

'... saw under the altar the souls of them that were slain for the word of God, and for the testimony which they held ...'.

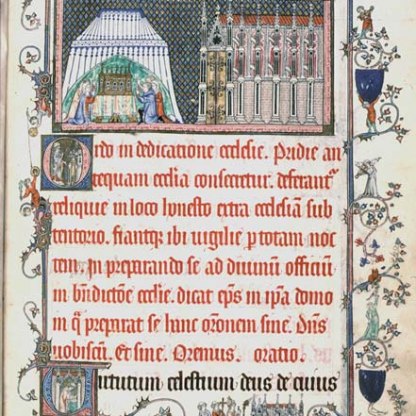

Inspired by this, the second Council of Nicea in 787 decreed that no altar could be consecrated without its own relics. A manuscript in the Fitzwilliam known as the Metz Pontifical, a book which details the various ceremonies to be performed by a bishop, shows the insertion of relics into a newly dedicated altar [MS.298.f.46r]. The ruling at Nicea still applies in the Roman Catholic Church today.

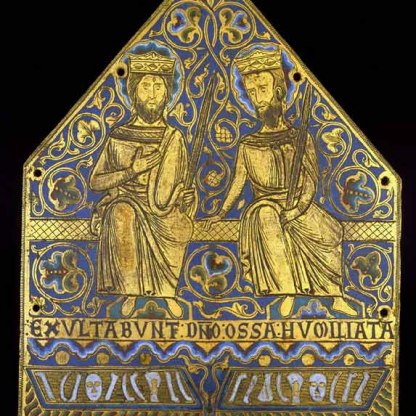

As is particularly apparent in the decoration of the Fitzwilliam reliquary panel, the relics of martyrs reminded the medieval worshipper of the promise of bodily resurrection. No matter how dismembered the saint, no matter how widely distributed his or her bodily parts, it was believed that, when the Day of Judgment came, the body would be made whole once more.

Because of the ambiguous position of these saints – their bodily parts on earth, their souls in heaven – they were in the ideal position to intercede between God and Man. The experience of praying to a favourite saint was intensified if he or she was somehow physically present. Relics were aids to faith, tangible evidence of salvation.

Certain relics became the focus of pilgrimage, and were credited with miraculous cures. And the most important ones acquired an economical and political significance, as well as a spiritual one. In the early ninth century, the Venetian state, wishing to increase its civic reputation and to give credibility to its claims as a major European power, stole the relics of the Evangelist Mark from Alexandria. There were many such examples of furta sacra – sacred theft – in the middle ages: Hugh, a twelfth-century bishop of Lincoln, who would himself become a saint, once bit off two fragments from the arm of Mary Magdelene when visiting this relic in France.

Given that the materials of most relics – bone, wood, cloth – often had little intrinsic value, the scope for forgeries was wide. A Church Council in 1215 tried to legislate against the trade in fakes, and decreed that henceforth all relics had to be authenticated by a bishop. But problems persisted. In The Canterbury Tales, composed in the late fourteenth century, the English poet Geoffrey Chaucer gives a vivid portrayal of a pardoner, a dealer in relics. This grotesque and sinister character is quite blatant in his admission of fraud, his peddling of animals bones to ignorant rural churchgoers, and his exploitation of popular superstition.

Over a hundred years later, Martin Luther complained about the profusion of relics and the absurd claims being made for them.

What lies there are about relics! One claims to have a feather from the wing of the angel Gabriel, and the bishop of Mainz has a flame from Moses’ burning bush. And how does it happen that eighteen apostles are buried in Germany when Christ had only twelve?

In 1555 at the Council of Trent, the Catholic Church, responding to the accusations of the Reformation which rejected relics, forbade their sale altogether.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…